Erected in the open air, monuments impose a memory on the public space that reflects the ideology of the people who promoted them. They are also exposed to the elements, suffering from the abrasion of the sun and precipitations in winter. While bronze monuments eventually rust, the destiny of those made of stone is to be covered with a verdigris patina. Combined with the solemnity of the forms raised on pedestals, this wear and tear seems to bear testament to a distant glorious past, although it’s not always the case. For example, right here in Móstoles the monument to Andrés Torrejón might look like it dates from a kingdom lost in time, but it’s only just over a hundred years old.

At the same time, not everyone has the right to this type of representation. Take a stroll through Móstoles and you’ll see that a clear hierarchy governs the ideas and people remembered in the town’s monuments, which prompts us to ask what and who has the right to a monument, what kind of monument, and what type of aesthetic, material and scale. Monuments and their pedestals evidence the struggle to claim a presence in the public space.

In this session of Ciudad Sur, we invite you to visit different squares and parks with us and look for all kinds of monuments. We’ll be joined by Daniel Palacios González (born in Móstoles and a resident of Alcorcón), who has a PhD in art history and researches cultural heritage and memory.

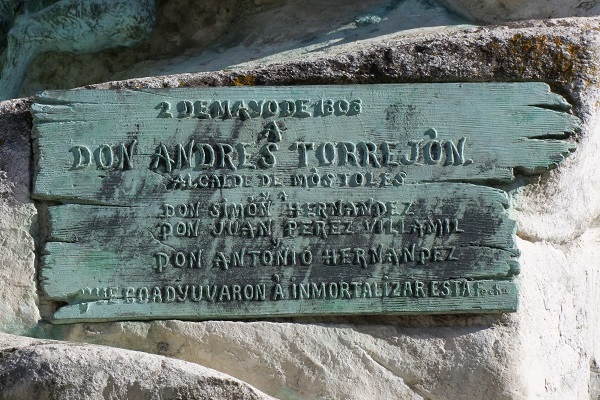

2th May 1808 – A Don Andrés Torrejón, Alcade de Móstoles, y a Don Simón Hernandez, Don Juan Perez Villamil y Don Antonio Hernandez, que coadyuvaron à inmortalizar esta fecha. Alta Falisa. Wikimedia